Elasticity (economics)

In economics, elasticity is the ratio of the percent change in one variable to the percent change in another variable. It is a tool for measuring the responsiveness of a function to changes in parameters in a unit-less way. Frequently used elasticities include price elasticity of demand, price elasticity of supply, income elasticity of demand, elasticity of substitution between factors of production and elasticity of intertemporal substitution.

Elasticity is one of the most important concepts in economic theory. It is useful in understanding the incidence of indirect taxation, marginal concepts as they relate to the theory of the firm, and distribution of wealth and different types of goods as they relate to the theory of consumer choice. Elasticity is also crucially important in any discussion of welfare distribution, in particular consumer surplus, producer surplus, or government surplus.

In empirical work an elasticity is the estimated coefficient in a linear regression equation where both the dependent variable and the independent variable are in natural logs. Elasticity is a popular tool among empiricists because it is independent of units and thus simplifies data analysis.

Generally, an "elastic" variable is one which responds "a lot" to small changes in other parameters. Similarly, an "inelastic" variable describes one which does not change much in response to changes in other parameters. A major study of the price elasticity of supply and the price elasticity of demand for US products was undertaken by Hendrik S. Houthakker and Lester D. Taylor.[1]

Contents |

Mathematical definition

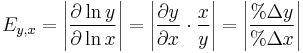

The definition of elasticity is based on the mathematical notion of point elasticity.

In general, the "x-elasticity of y" is:

The "x-elasticity of y" is also called "the elasticity of y with respect to x".

Specific elasticities

Elasticities of demand

- Price elasticity of demand

Price elasticity of demand measures the percentage change in quantity demanded caused by a percent change in price. As such, it measures the extent of movement along the demand curve. This elasticity is almost always negative and is usually expressed in terms of absolute value. If the elasticity is greater than 1 demand is said to be elastic; between zero and one demand is inelastic and if it equals one, demand is unit-elastic.

- Income elasticity of demand

Income elasticity of demand measures the percentage change in demand caused by a percent change in income. A change in income causes the demand curve to shift reflecting the change in demand. YED is a measurement of how far the curve shifts horizontally along the X-axis. Income elasticity can be used to classify goods as normal or inferior. With a normal good demand varies in the same direction as income. With an inferior good demand and income move in opposite directions.[2]

- Cross price elasticity of demand

Cross price elasticity of demand measures the percentage change in demand for a particular good caused by a percent change in the price of another good. Goods can be complements, substitutes or unrelated. A change in the price of a related good causes the demand curve to shift reflecting a change in demand for the original good. Cross price elasticity is a measurement of how far, and in which direction, the curve shifts horizontally along the x-axis. A positive cross-price elasticity means that the goods are substitute goods.

- Cross elasticity of demand between firms

Cross elasticity of demand for firms, sometimes referred to as conjectural variation, is a measure of the interdependence between firms. It captures the extent to which one firm reacts to changes in strategic variables (price, quantity, location, advertising, etc.) made by other firms.

- Elasticity of intertemporal substitution

- Combined Effects-

It is possible to consider the combined effects of two or more determinant of demand. The steps are as follows: PED = (∆Q/∆P) x P/Q. Convert this to the predictive equation: ∆Q/Q = PED(∆P/P) if you wish to find the combined effect of changes in two or more determinants of demand you simply add the separate effects: ∆Q/Q = PED(∆P/P) + YED(∆Y/Y)[12] Remember you are still only considering the effect in demand of a change is two of the variables. All other variables must be held constant. Note also that graphically this problem would involve a shift of the curve and a movement along the shifted curve.

Elasticities of supply

- Price elasticity of supply

The price elasticity of supply measures how the amount of a good firms wish to supply changes in response to a change in price.[3] In a manner analogous to the price elasticity of demand, it captures the extent of movement along the supply curve. If the price elasticity of supply is zero the supply of a good supplied is "inelastic" and the quantity supplied is fixed.

- Elasticities of scale

Elasticity of scale or output elasticities measure the percentage change in output induced by a percent change in inputs.[4] A production function or process is said to exhibit constant returns to scale if a percentage change in inputs results in a equal percentage in outputs (an elasticity equal to 1). It exhibits increasing returns to scale if a percentage change in inputs results in greater percentage change in output (an elasticity greater than 1). The definition of decreasing returns to scale is analogous.[5]

Applications

The concept of elasticity has an extraordinarily wide range of applications in economics. In particular, an understanding of elasticity is fundamental in understanding the response of supply and demand in a market.

Some common uses of elasticity include:

- Effect of changing price on firm revenue. See Markup rule.

- Analysis of incidence of the tax burden and other government policies. See Tax incidence.

- Income elasticity of demand can be used as an indicator of industry health, future consumption patterns and as a guide to firms investment decisions. See Income elasticity of demand.

- Effect of international trade and terms of trade effects. See Marshall–Lerner condition and Singer–Prebisch thesis.

- Analysis of consumption and saving behavior. See Permanent income hypothesis.

- Analysis of advertising on consumer demand for particular goods. See Advertising elasticity of demand

Footnotes

References

- Ayers; Collins (2003). Microeconomics. Pearson.

- Binger; Hoffman (1998). Microeconomics with Calculus (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley.

- Case, K; Fair, R (1999). Principles of Economics (5th ed.).

- Chiang; Wainwright (2005). Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics (4th ed. ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Curran, John (December 1999). Taking the fear out of economics. Cengage Learning EMEA. ISBN 9781861524744. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=iBFNU2eOPRIC. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- Dowling, E (1980). Introduction to Mathematical Economics (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780071358965.

- Gell-Mann (1994). "Is the measure of love the price of prostitution?". The Quark and the Jaguar. Holt.

- Goodwin; Nelson; Ackerman; Weissskopf (2009). Microeconomics in Context (2d ed. ed.). Sharpe.

- Houthakker, Hendrik S.; Taylor, Lester D.. Consumer Demand in the United States: Analyses and Projections. Harvard University Press.

- Kreps, D. (1990). A Course in Microeconomic Theory. Princeton.

- Kuehlwein. "Cocaine and the Elasticity of Demand". Manchester University. http://www.maths.manchester.ac.uk/service/resources/METAL/pdfs/differentiation/disc_ex.pdf.

- Landers (February 2008). Estimates of the Price Elasticity of Demand for Casino Gaming and the Potential Effects of Casino Tax Hikes.

- Mas-Colell; Andreu; Winston, Michael D.; Green, Jerry R. (1995). Microeconomic Theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Melvin; Boyes (2002). Microeconomics (5th ed.). Houghton Mifflin.

- Moffatt. "How Do We Interpret the Price Elasticity of Demand?". About. http://economics.about.com/cs/micfrohelp/a/calculus_i.htm.

- Negbennebor (2001). "The Freedom to Choose". Microeconomics. ISBN 1-56226-485-0.

- O'Sullivan, A.; Sheffrin, S. (2005). Microeconomics (4th ed.). Pearson.

- Perloff, J. (2008). Microeconomics Theory & Applications with Calculus. Pearson. ISBN 9780321277947.

- Png, Ivan (1999). Managerial Economics. Blackwell.

- Pindyck; Rubinfeld (2001). Microeconomics (5th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

- Research and Education Association (1995). The Economics Problem Solver. REA.

- Samuelson, W.; Marks, S. (2003). Managerial Economics (4th ed.). Wiley.

- Samuelson; Nordhaus (2001). Microeconomics (17th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Varian (1992). Microeconomic Analysis (3rd ed.). Norton.

External links

- Economics Basics: Elasticity from Investopedia.com. Accessed February 29, 2008.

- Revenue and Elasticity and Elasticity, Total Revenue, and the Linear Demand Curve by Fiona Maclachlan, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Introduction to Economics: Elasticity of Demand

|

||||||||